Mothers and Men

The Wind Rises

directed by Hayao Miyazaki

You were born in 1941, so that makes you something

like 73 years old. A ripe old age, to be sure. You were four years old, maybe three, when

The War ended. So you remember how your mother, maybe your grandmother, too,

scrambled 行 sold their precious kimonos, hiked miles to buy potatoes 行 to feed

you during and after The War. Maybe you knew the little girl who starved to death in

The Grave of the Fireflies. Or maybe your mother did. I was born a few

decades after you, so my experiences are second-hand. But my mother and grandmother, too,

were bombed out of their homes in air raids, so I grew up with the same tales.

The Wind Rises is beautiful 行 mesmerizing,

never once being preachy. In it you revisited a few of your major themes that have so resonated

with your fans: dreams of flight, and loss, and The War. Always The War, seen from the ground up 行

like our mothers saw it. This, to me, always seemed to oppose the other 行 the ascending momentum

行 and the two have been conflicting forces in your works. On one hand, you took us impossibly

high, with WWI flying aces, on a broom stick with a talking cat, or with a clan of pirates led by a

Walk焤e matriarch. The flights were even more exciting because we knew the devastations on

the ground: the post-apocalyptic wasteland of Nausicaä and Laputa, and even in Howl's Moving Castle誷 fairytale Old Europe.

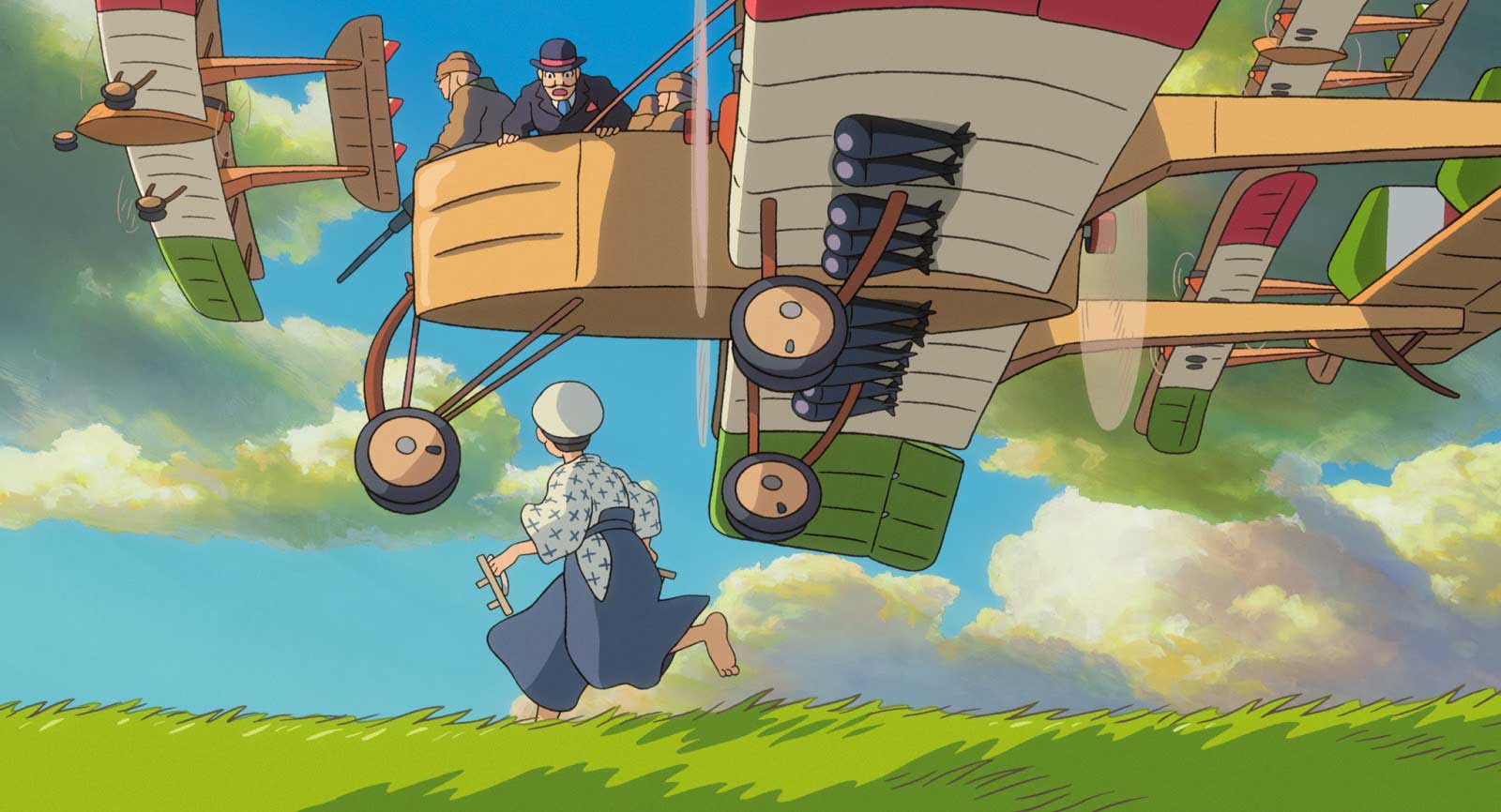

In The Wind Rises, you lift us so magically

with protagonist Jiro Horikoshi, the engineer of Japanese fighter planes in WWII, from the moment his plane takes off in his childhood dream.

You lead us to meet biomorphic bombs and the shadow people (whom we saw as minions of the

Witch of the Waste in Howl or chasing Chihiro in Spirited Away). And Italian engineer and Jiro's hero Giovanni Caproni, who

would become the boy's guide and inner voice throughout his career.

The sound was absolutely wonderful 行 adored the use of human voices for the sonic wave of the Great Kanto

Earthquake and the crescendo hum of aircraft engines. It gave, nature and machine alike, anthropoid qualities,

something to be respected and to be listened to.

Speaking of voices, your casting has always floored

me in its righteousness: You gave us Akihiro Miwa, the drag empress of Japan, as the giant

she-wolf/nature spirit in Princess Mononoke, as well as the elegant Witch in Howl. Former

Takarazuka male-role top star Y瀔i Amami was the sea goddess in Ponyo;

perpetual bad girl Mari Natsuki was Yubaba in Spirited Away. And you gave Jiro that flat, naturalistic

delivery of the father character in Totoro; the engineer's adult voice 行 after his posh and polite

childhood 行 astonishes at first, so accustomed are we to all the Disney overacting that turns

animated characters into, well, cartoons.

I loved the Magic Mountain subplot: the little paradise of calm in Karuisawa

resort and its TB sanatorium. My father spent some time in one, maybe right there, after the war. You introduce Mr. Castorp 行 whose first name

I am sure is Hans like the Thomas Mann character 行 digging into that huge bowl of watercress in the hotel's restaurant. It's

a sure way to make an impression: What is he? A pacifist vegetarian? Some Weimar progressive rawfoodian? An intellectual refugee from Nazi Germany?

|

Kamikaze pilots the day before their mission, May 1945. The oldest in the group, Kaname Takahashi, top right, was 18 years and 7 months old.

source: Wikimedia Commons |

What little complaint I have about the film entirely hinges on a single line spoken by

Caproni in the last scene. In a dream at the end of the war, Jiro and his mentor watch a flock of Mitsubishi Zeroes disappear over the horizon:

"They have nowhere to return to."

I understand that line is a logical extension of Castorp's warning: "Japan will blow up. Germany

will blow up." Jiro has had to deal with the military throughout his working life in the '30s, and the dramatic flourish is justifiable given the

devastation brought on by warfare to both countries. Heck, as far as men were concerned, both Germany and Japan had ceased to exist.

But that's a line you and I, both raised by women, their tales and actions, know the comeback to well enough:

"No, their mothers are waiting."

Your instincts led you to search the depths of our souls to put forth alternative views of history and mythology: history too old to be remembered and become

myths, and history yet to come and turned myths. You considered the unofficial history of Japan's indigenous people, the Emishis, and what they taught the

"conquering" Japanese about the spirits that dwelt in nature. You unleashed them in the parallel world Chihiro enters, from "her" world that's polluting the

waterways that were once spiritual arteries of Japan. And the protagonists were often girls 行 determined little girls way before Disney caught on and started

producing warrior princesses. And your women characters were leaders, rulers, business women and specialists. For all that, you are one great artist of our

time and I am grateful that I and my son have had you.

Yes, The Wind Rises is about men's dreams, in a world that was ruled and ruined by men. But mothers, sisters and lovers were waiting for those boys, aged 18, 19, maybe even 17, who were shipped off to die on the Zeroes.

I know my complaint is too small to bring you to reconsider your announced retirement.

Maybe it means it's our turn.

Mothers are waiting.

行 Rika Ohara

|