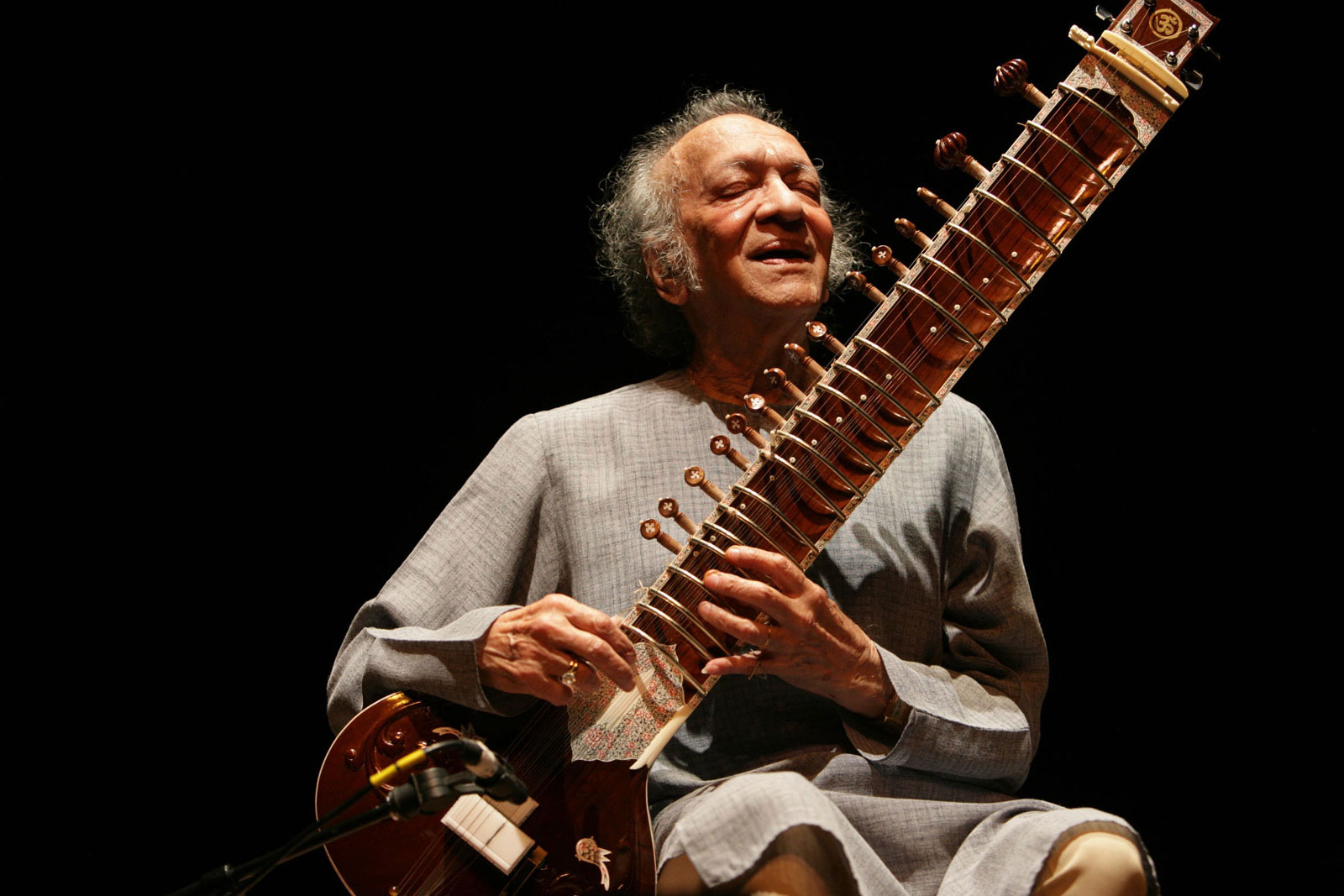

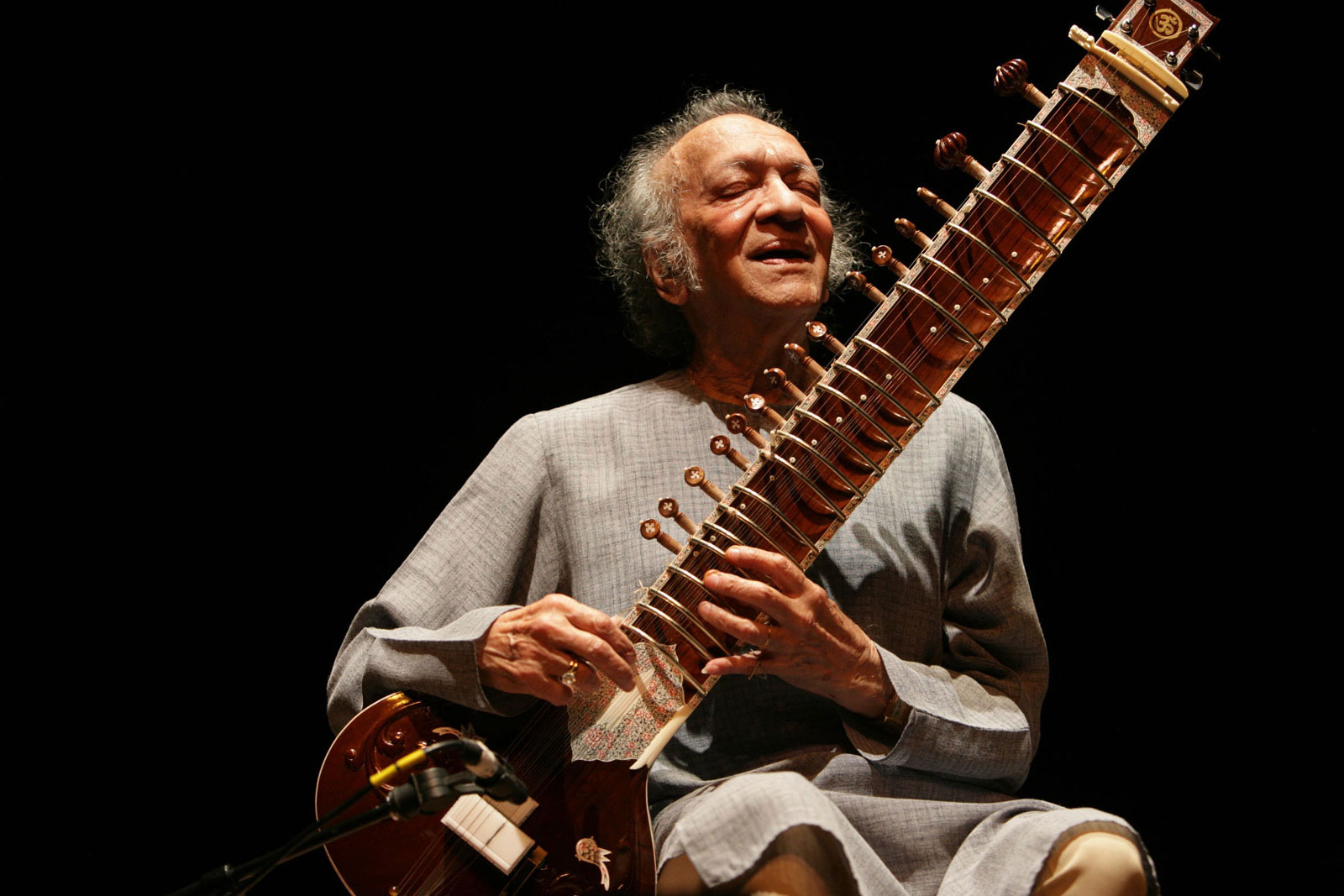

The Raga of Life

A conversation with Ravi Shankar

|

Indian sitar legend Ravi

Shankar has been an illustrious name since the mid-'60s, largely through his association

with George Harrison and the Beatles, whose music was profoundly influenced by ShankarÕs

mastery of the Indian classical raga form; his appearance at the Monterey Pop Festival and at

Woodstock in 1969 further spread the impact of Indian traditional music throughout the

Western worlds of pop, rock and jazz. (HeÕs equally famed these days as the father of singer

Norah Jones and sitarist Anoushka Shankar.)

To see and hear the 92-year-old Shankar perform is to witness a young old soul in a very pure state

of transformation. It is, he says, the eternally rejuvenating power of the raga that keeps him alive and kicking. Herewith, Shankar discusses his life

in music, and offers a tutorial in the nuts and bolts of his chosen form of expression, the raga.

BLUEFAT: Can you explain what a raga is, exactly? What is its shape and structure?

RAVI SHANKAR: IÕll try my best. [Laughs] I mean, you know Western music, donÕt you?

Yes. Well, a lot of it, anyway.

Oh, thatÕs wonderful. Then you know about the seven scales of the Grecian mode. Then let us start from there.

The ragas basically are melody forms based on scales, like the Grecian modes, but we have got a basic 72-note scale. There are ragas

which have seven notes ascending and descending, then there are six notes ascending and descending, and then not less than five ascending

and descending. So each of these ragas have their own ascending and descending scales. Some are just five notes ascending, five descending, or six or seven ascending and descending. Then there are combinations ŠŠ five ascending-descending, six, seven ŠŠ and then we also have the black notes and the ŅsharpÓ notes. It can go on and on.

How many ragas are there?

There are supposed to be more than 6,000 ragas, but in practice we deal with 100 to 150. I can without any problem think of about 200 different ragas ŠŠ but when I think about it I can think of even more ragas.

How can you possibly remember that many ragas?

After you ŅgetÓ this critical form of the raga, then you, the performer, learn from your guru, for years.

Because our learning is entirely person-to-person, it is not a written-down system. In the West you have this wonderful system of written-down music

by great composers like Bach and Beethoven, and then what a musician does is practice on his instrument the notes that are written down maybe a hundred years, two hundred years before. We arenÕt lucky to have that. We memorize all the different structures of the ragas, then create something like songs within these ragas with all the basic compositions which are already traditional and old. It takes longer to learn our music because it is all done by hearing and memorizing hundreds of thousands of things.

If the performer feels a passion for the music, all that hard work shouldnÕt be a problem, then.

After all this study, along with the talent and also patience and a fierce desire to prove himself after many years of learning from his guru, he can start performing on his own.

Where does the raga come from?

We have two different sets of patterns of ragas in India. One is the North style called Hindustani, to which I belong; and thereÕs a tremendous big operation of people in the South who play in the Carnatic style. Basically these systems are the same, but they separated 400 to 500 years ago. Because our music is very much based on songs with words, we have evolved within the Hindi world our own basic songs, and then in the South theyÕre structuring their songs around the Telagu or Tamil or other languages.

Tell me more about the Hindustani raga form.

With the Hindustani system, all the ragas are connected with the time of the day, like early-morning raga, late-morning raga, early-afternoon, afternoon, early-evening and late-night.

And then each raga is supposed to be like a certain person; they have personalities in the sense that they have their own special nature, or moods which we call rasa: Some are very sad, some are very happy,

some are very melancholic and some are very loving ŠŠ or angry. We instrumentalists have to maintain these rasa as much as possible. The performer makes associations with these moods and should or

can interpret them. Of course an artist has the freedom to play a different rasa that goes by, if he is competent enough.

How much of what we hear you play is improvised?

The improvisation becomes the tremendous developing part of our music. And here it depends on authority, it depends on musician to musician, and somehow the ability to improvise from less; I have always been very, very interested in improvising, and when I perform, whatever you hear is 85 to 90 percent improvised, on the spot.

When IÕm watching you perform, I wonder, Where is your mind when you are playing a raga? Or should I say, where is your heart, or your soul? Where are you?

It has to be completely affiliate to my own mind. I feel the notes, I can play with them, all the rhythmic varieties and the little ornamentations, and most of all itÕs a joy always to find out new things, try something which IÕve never done before and find that I can do it successfully.

My music, in the beginning it is always like a prayer, so here comes a lot of that divine sort of feeling. ItÕs like praying ŠŠ whatever religion you are, it doesnÕt matter ŠŠ there is that supreme feeling like a prayer, like seeing a different world of colors and beauty.

And then comes the part of showing off a little ŠŠ like all musicians we are showing off what we can do, the speed, the technical contest, you know.

And rhythm plays a very important part in our music. From the very beginning of this very simple song we can then go fast and very fast ŠŠ like any other good music, itÕs the world of speed and variety and rhythmic fun, which everyone loves.

How has your playing of the ragas evolved over the years?

To explain that, I should tell you some things about myself. I was born in Varanasi, a city known as the Eternal City, one of the oldest cities in the world. At the age of 10, my brother, Uday Shankar ŠŠ

he was a great dancer, and he was in Europe at that time ŠŠ brought me along with my friendÕs brothers, his mother and other musicians and dancers by train and ship to Paris, France. And for the next several years

we would travel all over the world, and I became a dancer as well as a musician.

You can imagine how lucky I was; at that tender

age I heard all the best music ŠŠ Andres Segovia the guitar player was our neighbor, he used

to come to our house; I met Fritz Kreisler, Jascha Heifetz,Yehudi Menuhin, most everyone in

the world of classical music, and the great Spanish flamenco musicians as well. And finally I heard jazz, which I fell in love with. Coming to America, it was wonderful. I heard all the great jazz musicians, went to the Cotton Club so many times, and such a fantastic experience I had.

But the war had started and I returned to India

in 1938. And it was only then, at the age of 15, that I started learning to play sitar properly,

from one of the greatest Indian musicians, Baba Allaudin Khan. I became his proper disciple

in the old style, with the simple life, avoiding all sort of pleasures and devoting complete

attention and time to practicing and learning. And thatÕs how I spent seven years with him.

It was completely a different life [laughs] than what I had enjoyed up till then, and it was very difficult for me, but at the same time I loved the music so much.

For your tireless promotion of the music and art of India, you have become known as a cultural ambassador.

Well, my whole career started when I was 35 and started coming on my own to perform in Europe and America and elsewhere. Because of all my childhood experience and being able to explain Indian music, like IÕm trying to do now, I was the only one who could do it at that time, unfortunately. This is how it started, you see, and IÕm happy that I could do it, for it opened the gates, and all our good musicians, young, old, started coming to perform here.

You have composed works for Western classical musicians such as

Yehudi Menuhin, Jean Pierre Rampal and Mstislav Rostropovich, and collaborated with

Philip Glass and George Harrison, among many others. Did those experiences change the way you heard your own music?

Exactly. And thereÕs one thing I would like to point out: You know it has been a big thing for the last several years for all musicians of different countries to experiment with the traditional styles of other countries. But I had always been very careful doing that; the only recordings I made were composed in pure Indian style for people like the Western-classical style violinist Yehudi Menuhin and the flutist Jean Pierre Rampal from France. But I never attempted to do something in the Western way.

With Philip Glass it was a different approach, where he just gave me two lines of a composition that he wrote and told me to do whatever I want, and I

did the same thing to him. I used mostly Indian instruments and a few Western instruments, and with the help of the ragas and all these different structures Philip Glass had given me,

it turned out to be something very interesting.

[Laughs] I think that I am not competent enough to play with flamenco or jazz or other Western-style musicians, and neither am I sure that they are competent to play in our Indian form, so I had avoided that.

Was George Harrison a good student?

George was a very good student. But he was so busy with so many things that he didnÕt really have any time to sit and practice sitar, you know. What he did was listen to me and my thoughts, my expressions ŠŠ he got the spirit of ragas and our music in a fantastic way, because he was so interested in our religion; he loved the old Vedic philosophies and structure of our society, the way we conceive God or whatever.

But apart from that, he was the dearest friend, he was like a son, like my younger brother, friend, everything, and I miss him very much.

Can you remember what it was like performing at the Monterey Pop fest, at Woodstock, or the Concert for Bangladesh? Was there a bit of culture shock for you?

At Monterey, I saw this change, with hippies and beards and beads and patchouli and things like that. And I was charmed in the beginning to see all these beautiful people, young people giving flowers ŠŠ peace ŠŠ and it was such a lovely thing. The festival was full of all the top names in the pop and rock worlds, you know, and there were a few bands who impressed me very much, like Simon & Garfunkel, Otis Redding, the Mamas & the Papas, Peter, Paul & Mary. These people really had some music which touched me very much.

Then next there were big rock groups, and IÕm not saying anything against them, but you know I have a little problem with really loud sounds, and

sitting very near the stage with the loudspeakers and the big rock bands, it was affecting

my heart! [Laughs] I was trying to appreciate it, but then many people they started breaking their instruments, and then someone started burning the guitar. And all of that made me soÉI almost choked, crying, and I wanted to leave. I told the person who had chosen me that I cannot perform here, IÕm sorry, please!

But your performance at Monterey became the stuff of legend.

They persuaded me to stay, and two days later fixed an afternoon performance for me specially, with no one playing before or after me. And that performance happened to be so wonderful and so inspired. It was beautiful. And all the famous musicians of those days were all sitting there. Fantastic.

Then came Woodstock. To me it was a very strange experience because it was raining and I had difficulty, and I told them to cover up the stage as much as possible. And then I found out that it was half a million people there, and it was mud they were sitting in. Yet they heard this music and seemed to be enjoying it. That was really unique.

But I must say that since then IÕve stopped performing at these big festivals. I was misunderstood, because of the drugs. While the young people at

Woodstock loved me so much, I tried to make them understand that they had the wrong conception. And now we have, unfortunately, places like Juarez, Nepal, and many other places where things have got mixed up with a lot of things which are not really meant to be. And this is what I wanted to make clear, that our music doesnÕt go along with this.

How do you see the path before you?

IÕm 92, and my mind is not changed. I feel just as I did at 16, or, you know, 18! [Laughs] IÕm very active. I try to teach, and IÕm writing as much as I can, and I still like to perform

ŠŠ thatÕs the main thing. I want to keep as much as possible the really important things.

photo by Michael Collopy

|