What He Really Wanted To Do Was Direct

My F焗rer directed

by Dani Levy

Adolf

Hitler's relationships with artists is a subject that continues to fascinate

other artists 行 Mephisto (1981) and Hanussen (1988), both directed by Iztvan Szabo and starring

Klaus Maria Brandauer, come to mind, not to mention the real-life saga of

Leni Riefenstahl. Of course Hitler

himself was a failed artist; then there

were the spectacular theatrics of the Nazi regime that mesmerized the

German public and bestowed them with illusions of grandeur.

In the Szabo films, Hitler is a distant, almost mythical

figure whose ascension to legend the artist unwittingly assists (in Mephisto, Brandauer's actor character

sells his soul and becomes one with the cosmic Enabler he portrays

onstage). In writer/director Dani Levy's My F焗rer, on the other hand, the

artist meets Hitler in his twilight (four more months to go), and we get

closer to the F焗rer 行 much, much closer, sharing a shrink's couch, cot

and blanket.

A black sedan speeds through a bombed-out Berlin, its jagged

edges exaggerated by a wide-angle lens. It's Christmas 1944, five months

after yet another assassination attempt. The Russians are in Slovakia;

France and the Netherlands are long gone. Despite the delusions his coterie

feeds him daily, der F焗rer is a nervous wreck: paranoid, bloated and

hopped up on amphetamines. The scheduled New Year's address is five days

away and his handlers desperately want that old Hitler magic back. Goebbels

comes up with a final solution: He pulls Professor Adolf Israel Gr焠baum

(Ulrich M焗e, The Lives of Others), a renowned actor, from the Sachsenhausen camp

(Goebbels apologizes: "I thought we had put you up in Terezin, that's our nicest

camp") to coach Hitler. The prisoner is brought to headquarters, where

soldiers and officials alike try to comprehend the unusual visit. Heil

Hitlers are hastily exchanged in panic; the German language has

never sounded so ridiculous.

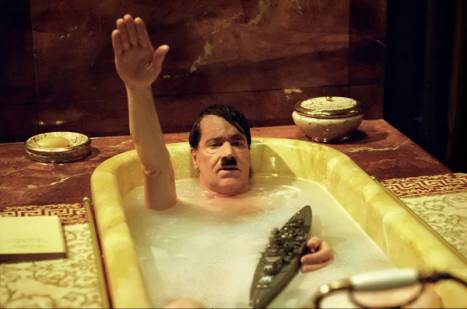

Helge Schneider's Hitler, far from the agile

Charlie Chaplin

in The Great Dictator, just about stirs sympathy. Sylvester Groth confirms

Goebbels 行 the multimedia orchestrator of propagandas, and the real power

junkie 行 to be a womanizing sleazeball. But the true star of the film is

M焗e. His Professor Gr焠baum is an artist caught between his

professionalism and his humanity. Just as Dirk Bogarde would have done in

the role, M焗e imbues his character's emotional turmoil with intelligence and

dignity. Professor Gr焠baum knows what makes Hitler tick, and instructs his

pupil to get in touch with his hatred. Gr焠baum bargains with Goebbels to

save his family and risks them again to have all of his fellow inmates

released, then, when his wife tries to smother a sleeping Hitler with a

pillow, he defends his pupil by saying, "He was an unloved

child!"

With that peculiar little mustache, bacon-grease-pasted hair

and hysterical mannerisms, it would have indeed been easy to make yet

another Hitler cartoon 行 and ridicule, like violence, is a product of

hatred. But it was the coexistence of revulsion and empathy that made

Chaplin's Dictator great. Levy plays it straight, until it is impossible not

to laugh; he knows there are situations whose horror reaches absurd

proportions. M焗e

is a master of ambiguity when his character, in the end, turns Hitler's

speech into a mass self-affirmation rally. Did he succeed? Did he fail? We,

65 years later, know what would soon befall the tyrant 行 but that's an

infinitely rich moment afforded us by the luxury of time.

行

Rika Ohara

|

|